A Bushel and a Peck: Growing Island Vegetables

Market gardens and farms have sustained islanders from the earliest people to Gold-Rush hopefuls, soldiers, settlers and sailors

(Photo courtesy of the Town of Friday Harbor)

Local restaurant menus tell just the current chapter of a long and varied story of the humble vegetable in the San Juan islands.

Today, the carrots, kale and peas on your plate could be from a dozen different farms on Lopez, Orcas or San Juan Island – but the San Juan Islands have gone through many changes and challenges with regards to growing and selling the bounty of farm crops we now see everywhere in local restaurants, farmers markets, food-coops, and a growing off-island market.

Native people sustained themselves by following the harvest, gathering berries and shellfish in season, managing fields of camas root, and hunting and fishing throughout the islands. In the mid-19th century, European settlers and farmers struggled and strategized to find the right crop and produce a profitable herd or harvest, raising potatoes, turnips, peas, oats, wheat and had orchards of apples, pears, plums and cherries. In the 1850s, one of the the first big demands for San Juan Island products was from the influx of hungry miners that stopped at Victoria on their way north to strike it rich on the Frazier River. As new markets were found, sheep were shipped to Vancouver Island, fruit was barged to Bellingham and beyond.

Since the late 19th Century, advertisements targeting potential settlers back east touted the islands as an farmer’s paradise, much like California was promoted. As early settlers came west, either in search of land, jobs, and gold, these messages influenced how settlers saw the islands. In a 2004 National Park Service Environmental History project, Christine Avery combed through old brochures, newspapers, reports and personal histories to get a sense of how farmers were lured to the islands:

“In newspaper articles and promotional supplements aimed at mainland residents, writes Avery, San Juan Island’s boosters promoted the island as a potential Eden. They called the island “the most delightful, charming and productive” on earth, and they believed that San Juan possessed natural advantages that ensured agricultural success.

Charles McKay and Thomas Fleming typified the early island settler. McKay, a failed gold miner and one of the first settlers on San Juan Island, was attracted by market hunters’ reports of the island as he journeyed back from the Fraser River gold fields to California. He recalled, “They told us what a fine island it was, full of game. So we went to see it. There appeared to be a lodestone on the island, for we got stuck at once.” The Nova Scotia native claimed 160 acres as his own and began farming.

Another account read, “Here, fanned by cool sea breezes in summer and experiencing none of winter’s intensities, (island farmers) live an ideal life amid an ideal environment. Here, there are no high water rates as in irrigated sections, no sand storms, cyclones or cloudbursts as in the Middle West.”

As more settlers arrived, the search for which crops grew best ensued. Orcas Island became known for abundant orchards of apples, plums, cherries, apricots and more. On San Juan Island, potatoes, oats, wheat and peas were seen as promising cash crops.

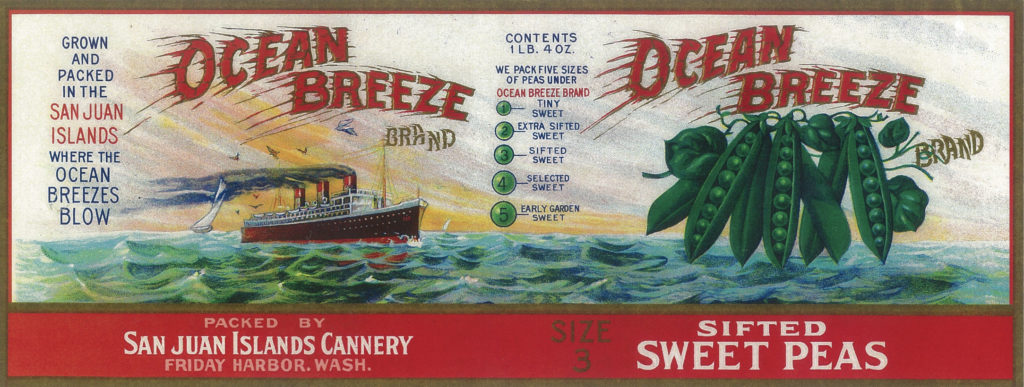

(Image courtesy of the Town of Friday Harbor)

Dry peas were long a farm staple, but peas for canning were introduced in the early 1920s. According to Avery, John M. “Pea” Henry grew peas on 1200 acres in San Juan Valley, and ran the “Saltair Peas” cannery in an old salmon cannery in Friday Harbor, which eventually employed 150 workers and canned 50,000 cans a year. The crops were abandoned in 1939 after a pea weevil infestation, but revived in 1956 by George Jeffers and his associates, who operated the Friday Harbor Canning Company. They grew peas on 450 acres, but this time chemical pesticides were employed – even dust cropping by airplane. The last peas from this farm were harvested in 1966. During this time, Avery writes, a variety of other crops, such as filbert nuts, walnuts, peaches, grapes, ginseng, potatoes, wheat, and oats, were grown commercially on the island, but none of enjoyed the success of the orchard fruit and pea industries. (Coho)

During the early settlement of the island, homesteaders would row or sail their goods to nearby markets in Victoria or Bellingham, but steamboats began daily ferry service in 1923. “Stopping at the many small hamlets and villages where farmers could take their goods, this informal system became known as the Mosquito Fleet, and served as an important connection and source for freighting.” (Coho)

Many islanders resisted the transition from a rural to a tourist economy, but some saw economic opportunity in the change. By 1908, developers were building summer homes on former orchards. One early twentieth century promotional paper reminded potential visitors that the island was “first and foremost the home of the stockraiser, the dairyman and the fruit grower,” but islanders were beginning to see the economic value of attracting tourists. Sociologist Norman Haynor reported, “Farmers who own beaches on Orcas Island dream about the resorts they are going to establish, and storekeepers talk about a golf course and an automobile road up Mt. Constitution.” Other island farmers and merchants eagerly viewed tourists as consumers for local products. As fitting an agricultural community, promoters boasted that the island’s fresh foods, such as meat, cream, eggs and vegetables, “will build up (the tourist’s) constitution that he may return to work with renewed strength.” These islanders hoped that tourists would invigorate the archipelago’s economy. (Avery)

This final prediction is one that is currently coming true. While early farmers focused on one or two cash crops, such as potatoes, peas, oats, or orchard fruit, farmers today cater to visitor’s tastes and experiment with diverse crops from around the world such as Japanese greens, cippolini onions, microgreens, purple carrots, dinosaur kale, lemongrass, horseradish, ginger, fingerling potatoes and orange tomatoes to sell to restaurants, co-ops and at farmers markets.

Now diners ask for organic, and focus on freshness. Chefs create gourmet meals from nutrient-packed veggies that were picked that morning on a farm just miles a way, and artisan producers preserve the bounty in sauces, preserves and other gourmet products.

So much has changed, but the one thing that is certain is that the farmers of the San Juan Islands will continue to adapt to shifts in the economy, environment and culture, finding a way to sustain themselves and those who love to eat what they grow.

—Shannon Borg

Almira Boyce and Her Sister Mary on Little Road, Circa 1916. Photo Courtesy of San Juan Historical Museum

Thank you to the Town of Friday Harbor, agricultural historian Boyd Pratt, Anna Maria de Freitas and Coho Restaurant’s blog, and the National Park Service for information compiled in this article.