The Wild & Woolly History of Sheep in the San Juan Islands

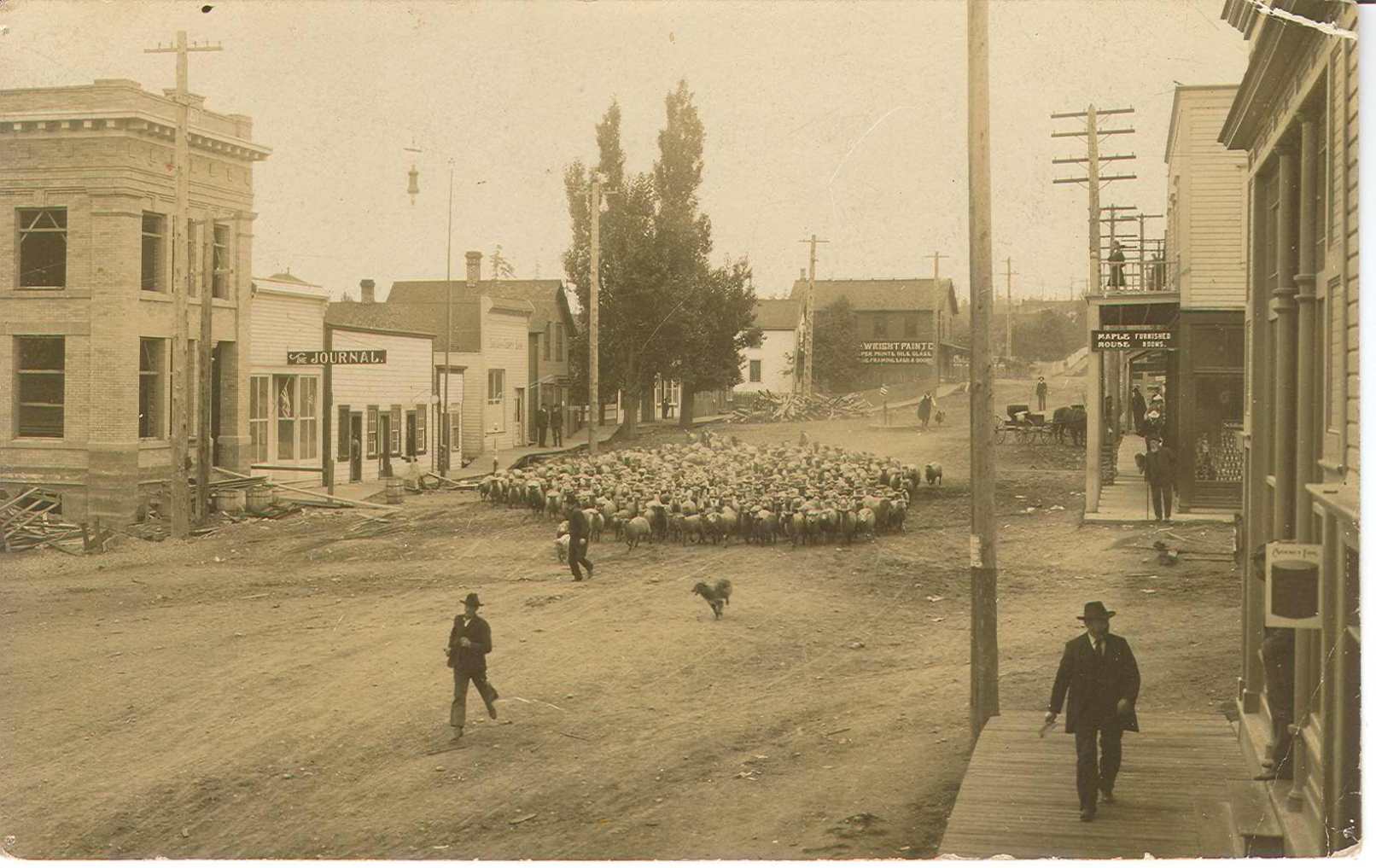

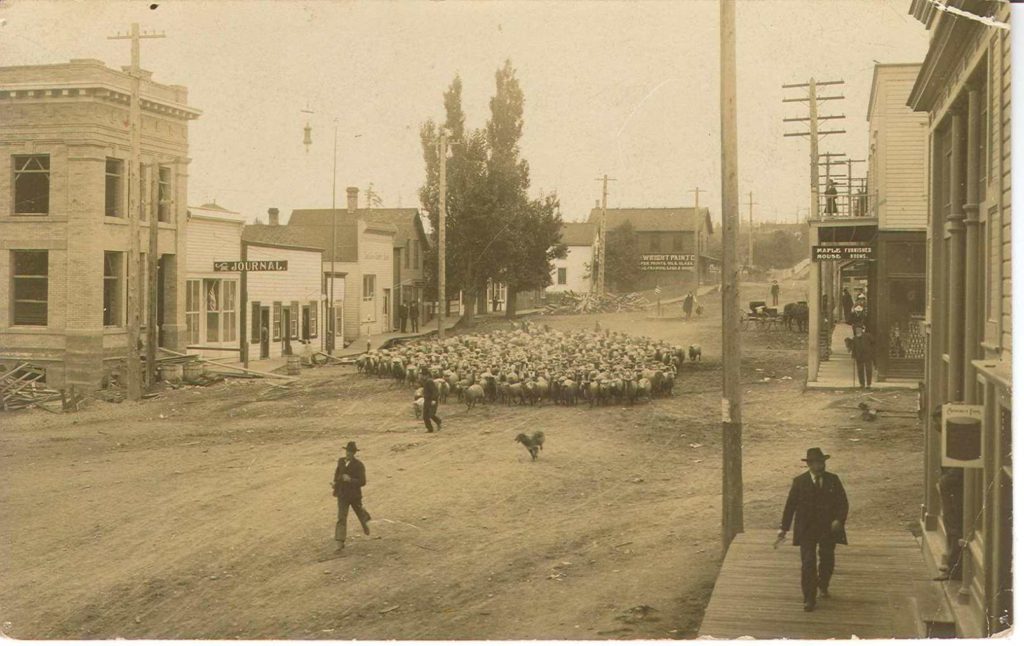

From barging rams to the outer islands to running sheep through the streets of Lopez Village, the history of wool in the San Juans is a warp and weft of ingenuity and tall tales

NAMING ISLANDS, RUNNING SHEEP

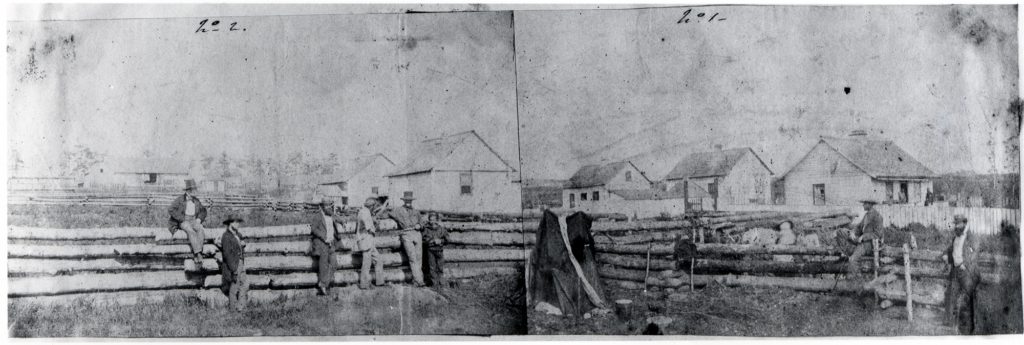

Raised for breeding, meat, and wool, sheep have always been a major part of agriculture in San Juan County. More than 160 years ago in 1853, Charles Griffin of the Hudson’s Bay Company brought 1,369 sheep to the newly-established Belle Vue Farm on the southern end of San Juan Island, in what is now American Camp. The company built up their flocks to more than 4,000 animals, and American and British settlers also soon established large flocks.

For local farmers in the ensuing decades, island living brought with it special challenges. In his book Island Farming: Agriculture in the San Juan Islands, local historian Boyd C. Pratt shares some of the ways farmers adapted:

“One of the ways to control open-range sheep was by taking advantage of the unique geography of the archipelago: the use of small islands for sequestering rams. The names “Sheep Island” or “Ram Island” (located between Lopez and Decatur), stem from this use.”

Dinner Island and Brown Island were used exclusively for sheep. In 1874, a surveyor wrote, “Dinner Island is claimed by Fred Jones, who makes use of it for pasturage for ‘Rams’ for which it is well adapted, as it is covered with rank growth of bunch grass.”

The main flock of ewes and wethers were kept on larger islands, and the rams rowed over during breeding season. The Salish peoples used the same strategy for sequestering skéxe, or woolly dogs; to keep their animals’ lines pure, upper class women would keep their packs on smaller islands, canoeing out to feed them every day.

The Hudson’s Bay Company had special systems to distribute and gather the thousands of sheep they kept throughout the island.

“There being no grass or other food for the sheep in the wooded Districts, the sheep stations are, from necessity, placed in the natural prairies of the Island; which are distant from each other, and connected by roads, opened with much labour, through the forest…” (National Park Service)

Many of the island’s roads today trace the paths of the sheep runs carved through forest and around the tremendous rocks left behind by the glaciers. A few of the prairies are still in use for grazing, though in some cases sheep have given way to alpacas, which pay more per acre. (NPS)

Wool was big business, enough so that the conflicts over HBC sheep being stolen came to a head at Belle Vue Sheep Farm in an incident that helped foment “The Pig War” conflict. According to the National Park Service:

“In the first two years of the farm’s operation Griffin was besieged by federal customs officials and county tax collectors, (who) went so far as to hold a “sheriff’s sale” on the beach below Home Prairie and abscond at gunpoint with 35 breeding rams. An international incident ensued which calmed down only when the President of the United States gave his assurances that British property would be respected. Nevertheless, U.S. customs inspectors regularly called at San Juan to keep book on Griffin’s operation in anticipation of the day the islands became U.S. possessions.”

LAMBING ON LOPEZ

For years, Lopez Island sheep farmers have also run their sheep through the Village or down main roads from one pasture to another as the seasons changed. Lifelong islander Valerie Yukluk carried on her family’s tradition of sheep farming for many years.

By the time Valerie’s father, Pierre Franklin, came to Lopez Island in 1947, the number of sheep in the islands had decreased by almost half, from its highest level of 18,789 in the 1930 census, to just over 10,000. Pierre raised mostly sheep, along with some cows and horses, first on his own farm that he bought on Cousins Road and later on other farms on Lopez.

Valerie’s best memories of sheep farming are intertwined with childhood memories of riding bareback on their family’s Welsh ponies.

“The most we had ever was 13,” Valerie recalled. “It was pretty fun because not a lot of the other kids on the island had horses or ponies, so we could catch a bunch of ‘em and go ride. My sister and I mostly rode bareback but for friends we’d put a saddle on them. And we had some wild ponies!”

So for Valerie, what’s the hardest part of sheep farming?

“We had pretty good luck lambing, except a couple of ewes got mastitis,” Valerie said. “Trying to deal with a sheep with mastitis is hard.”

Valerie, who turns 64 in June, says she’s starting to cut back on sheep farming, even as another type of farming garners her attention—working with the kids at the local school where she sees her role as passing on the knowledge she grew up with.

THE FUTURE OF FARMING

With the island economy shifting from agriculture to tourism, the number of farmers keeping sheep has been declining. Now, many farms are a draw for families who love to visit local farms, see baby lambs, and buy local products such as lamb, beef, pork, cheese and fresh vegetables. And there is also a small but passionate population of sheep lovers, wool fanatics, weavers, knitters and others that are keeping sheep farming alive in the islands.

For Valerie, the hope for the future of farming in the San Juan Islands lies with future generations, and she feels a duty to pass on the love of growing your own food, and farming in general.

“It’s hard for young farmers to buy property, but there seems to be a lot of people to let them use their land and do things,” Valerie says.

“It’s changed a lot since I was a kid. When I grew up, everybody had some animals–chickens, or a cow. Most people had some kind of connection to the farm.

“Now there’s just a lot more people and that knowledge is what we’re trying to keep going at the school: connect the kids to where their food comes from.”

At Lopez Elementary School, Valerie works with kindergarteners in the garden. “We raise 60 percent of the school’s food,” she says. “We make tomato sauce and pesto and freeze it and they use it all year. We grew dried beans and corn, ground it and made cornbread.”

Does she think any of her students will become farmers?

“Oh yeah for sure,” she said. “Two boys at the school bid on fields to cut, bale and sell hay. They started their own little hay business.”

“I’m happy that we have children coming up that are going to keep it going.

*

Compiled by Amy Herdy, Boyd Pratt and Shannon Borg, with information courtesy of the National Park Service

*

Island Grown in the San Juans is gathering stories from the fascinating history of farming in the islands. We will be sharing these stories to keep our history alive and help us all remember what has made our islands so unique.

Order the San Juan County Farm-to-Market Guide and Product Guide.

Join Island Grown today – as a farmer, retailer or supporting member.